Every year, more than two billion farmers around the world work the land day in and day out to earn a living and produce what is needed to feed and clothe an ever-growing global population that reached 8 billion in November 2022. Though they bear the brunt of climate change on the front lines, many of the world’s farmers, ranchers and fishers are unaware of the international processes that affect their livelihoods.

|

“The decisions made this year at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, encompassed mitigation, adaptation, the allocation of resources and new agreements on loss and damage and are of vital importance for the world’s farmers.” |

The most important of these global events is the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where over 30,000 people engage in high stakes negotiations, advocacy, and communication. The debates undertaken and the decisions made this year at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, encompassed mitigation, adaptation, the allocation of resources (capacity building, technology transfer and finance) and new agreements on loss and damage are of vital importance for the world’s farmers.

The connection between climate change and agriculture are written into the foundations of the climate accord. The preamble of the Convention states that greenhouse gas concentrations should be stabilized “within a time frame sufficient…to ensure that food production is not threatened.” Yet this goal has not yet been accomplished. Agriculture and food systems face very high levels of climate risk, and depending on how emissions are sliced and diced, also can contribute up to a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet for many years agriculture has not had a significant presence in the national and international climate processes.

Yet as COP27 ended and the 2022 World Cup began in Qatar, it is not a stretch to say that this was the year when agriculture finally got off the sidelines and onto the pitch. There was a strong push by many public, private and civil society actors for agriculture to have a stronger presence and voice both within and outside the negotiations in Egypt. And within the negotiations themselves, a very important agreement was achieved by Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture (KWJA) negotiators and adopted by the COP to extend the agenda item on agriculture for four more years. The sense that the agriculture and food security constituency was now a starring player in the game was inescapable.

|

“There was a strong push by many public, private and civil society actors for agriculture to have a stronger presence and voice both within and outside the negotiations in Egypt.” |

A Growing Presence

Outside the formal negotiations, there was an incredible drive to have food and agriculture front and center. The Egyptian COP27 Presidency dedicated one of its thematic days to adaptation and agriculture, with a full program of high level panels drawing attention to the KWJA and other relevant issues, including food security and nutrition, technologies, adaptation, finance, private sector support.

There was no shortage of proposals. The COP27 Presidency, together with FAO, launched the Food and Agriculture for a Sustainable Transformation (FAST) Initiative to improve the quantity and quality of climate finance for agriculture and food systems by 2030. Another new program announced—I-CAN, the Initiative on Climate Action and Nutrition—promises to accelerate transformative action to address climate change and nutrition challenges. Global investors asked FAO to produce a roadmap to 2050 to align the Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use sector with a sustainable 1.5 degrees Celsius pathway.

Other broad proposals in the sector include the Agriculture Innovation Mission for Climate (AIM4C), an initiative co-facilitated by the United Arab Emirates (host of the COP28) and the United States, revealed a doubling of investment commitments from 42 member governments to $8 billion for supporting innovation for agricultural adaptation and emissions reductions. The European Commission, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United States collectively also committed $135 million in new funding for the Global Fertilizer Challenge, to support fertilizer efficiency and soil health programs to combat fertilizer shortages and food insecurity.

Individual nations are also stepping up. The Minister of Agriculture of Chile, Esteban Valenzuela, announced the First Net Zero Food Systems Ministerial Summit to be held in Chile in March 2023. The Foreign Affairs and Agriculture Ministries of New Zealand will invest $10 million in a four-year Climate Smart Agriculture program in Latin America and the Caribbean. Tom Vilsack, Secretary of the USDA, announced that the US will establish an international climate hub to share information and promote science based action.

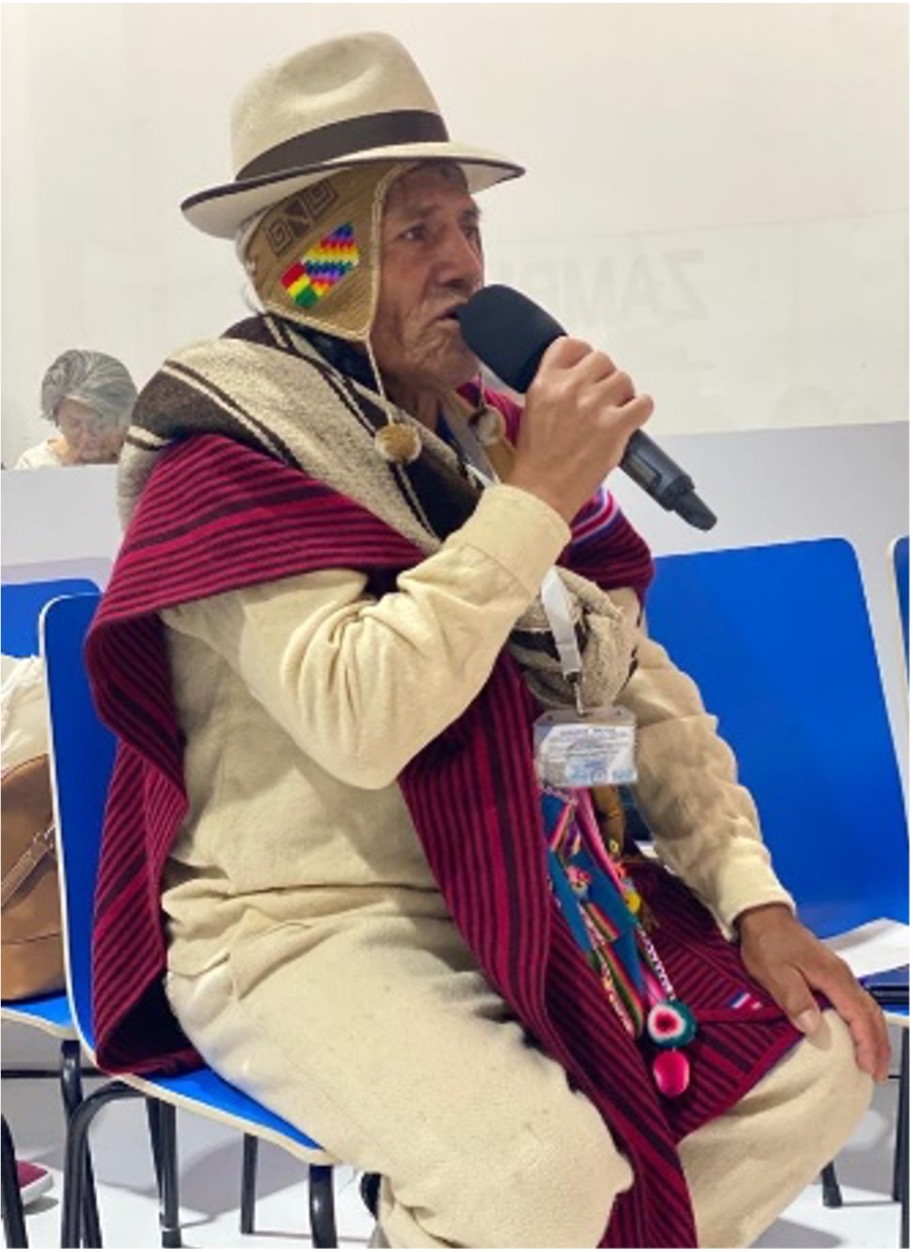

The momentum came from other parties as well. Messages from the Ministries and Secretaries of Agriculture of the Americas demonstrate increasing political will for engagement by the sector in climate action at the international and national levels, and for advancing the implementation of the National Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans. The Nairobi Work Program and Global Stocktake both held small breakout groups focusing on agriculture in their broader consultation events. And the farmers constituency, led by the World Farmers Organization, held meetings every morning for representatives of farmers organizations. Over 150 farmers attended—including indigenous farmers from Bolivia, youth farmers from Uganda, no till-farmers from Argentina, and women farmers from the Philippines.

|

“Increased visibility also came from a number of the first ever agriculture and food-focused pavilions. (Not one, but five of them!)” |

Increased visibility also came from a number of the first ever agriculture and food-focused pavilions. (Not one, but five of them!) The Sustainable Agriculture of the Americas Pavilion led by the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture, the ministries of agriculture from 34 countries of the Americas and many private sector, farmer and civil society organizations elevated the participation and voice of agriculture in the climate discussions and highlighted the importance of the Americas for feeding the world. Other centers of activity included a Food Systems Pavilion that focused on the entire food value chain, a Food and Agriculture Pavilion organized by led by FAO, The Rockefeller Foundation and CGIAR to put agrifood systems at the heart of the COP27 agenda, an IFAD Pavilion that amplified the voices of small-scale producers, and a Food4Climate Pavilion that examined food system transformation and sustainable diets.

Coming to Consensus

Within the formal negotiations, there was also a strong push for agriculture. The Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture required about a decade of negotiation before it was established in 2017, and a series of 12 workshops were held during its first period. Many international organizations provided both structured (workshops and trainings) and informal discussion spaces (dialogues and dinners) in these years, as well as opportunities for negotiators to interact and build capacity. Yet when KJWA´s first period was completed in 2020, what followed was almost two years of inability to propose a consensus summary of what was achieved and a way forward.

Failure to renew the KWJA would have most likely meant the dormancy of the unique space, which does not fit neatly in the boxes (mitigation, adaptation, technology, finance, etc.) of the economy-wide way the UNFCCC is structured. So the agreement at COP 27 to extend the agricultural agenda item for four years is momentous milestone. And it almost didn’t happen. Dozens of extra hours of grueling negotiations—between global entities, and also within the G77+China and other negotiating groups—were required to reach agreement. This tremendous dedication, creativity, and effort of negotiators from all regions and commitment of the COP27 Presidency have breathed new life into the space. Exhaustion and frustration throughout the negotiations were palpable, but there was no denial of why this work to address climate change in agriculture is so important. There were only questions on structure and how to focus the space in a productive, non-duplicative way.

No text is perfect, but the COP27 decision to establish a four-year Sharm El-Sheikh Joint work on implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security recognizes the limited resilience of global food systems, vulnerability and role of smallholders, the need for context specific solutions, and the work accomplished through previous workshops. It offers a way forward, and a better balance towards the “implementation” side of the joint work. The new agreement also establishes a reporting process from and links to the UNFCCC’s constituted bodies and financial entities, as well as establishing both periodic workshops and development of an online portal with information projects, initiatives and policies for agriculture and food security to support implementation.

Some observers have expressed disappointment that a broader food systems approach was not included in the new work. However, because the highest vulnerability is found in production systems, and almost three-quarters of emissions stemming from production (agriculture and land use change), it makes sense to focus first on this particular part of the value chain. Many things are happening outside formal negotiations, and a consensus-based process take much longer and involve compromise. But the work accomplished in Egypt provides stronger, binding decisions with accountability for all parties.

The KJWA is not the only space that holds importance for agriculture and food security, and many decisions were taken at COP 27 have relevance for these areas. The decision for new funding arrangements on loss and damage to support developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change, and the establishment of a “transitional committee” to help its operationalization, is one example. Weather events caused over $2.5 trillion in damages globally between 2011 and 2020. In developing countries, agriculture absorbs about a quarter of this, costing over $108 billion. Also of note is that between 2008 and 2018, the impacts of disasters cost the agricultural sectors of developing country economies over $108 billion in lost or damaged production according to FAO. Once operationalized, funds for loss and damage should help the sector.

|

“The quantity and quality of climate finance needs to improve and be better directed. Currently, only 10 percent reaches the local level, and under 2 percent goes to smallholder farmers.” |

The Road to the COP28 Dubai – With Many Stops Along The Way

There is still a long way to go to ensure the progress benefits the world’s farmers. As Antonio Guterres has said: “We can and must win this battle for our lives.” All the pieces of the puzzle are, to varying degrees, in place: partnership building, knowledge, finance, coalitions and initiatives. Yet we are still not getting the movement we need.

What remains to be done? The quantity and quality of climate finance needs to improve and be better directed. Currently, only 10 percent reaches the local level, and under 2 percent goes to smallholder farmers, undermining the efficacy and impact of resources. And the larger picture matters, too. Whether politicians and negotiators can agree to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius or not, it not merely a goal, but a real physical border. Going past it means that negative impacts, especially on food production, will leap. The world is currently on track to reach over 2.5 degrees Celsius, which would be “game over” for many of the world´s food producers. While life without fossil fuels is necessary, but life without food is impossible. Yet we also know that we can´t stay within that 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius limit without significant contributions from food systems. How can we better enable, accelerate, and support this without putting a target on farmers´ backs?

Agriculture and food security need to be front and center in the discussion and in tangible climate action—and also in it for the long game. A just transition must be a farmer focused transition. Agriculture and food system actors must inform international decisions, and not just on Koronivia. They have a role to play in developing policy and action on finance, mitigation, technology, transparency and, of course, adaptation. We know that the agriculture voice is not a homogenous one, so how can we make sure all are part of the debate?

In a hallway conversation, the Secretary of the UNFCCC, Simon Steill, observed that: “When we leave here is when the real work begins.” This rings ever so true for the two billion farmers—and of all us in the world who like to eat. The annual Conference of Parties itself is just one part of the process, an enabler, that sets a framework for national action. After the sun has set on the COP27, the real sign of success will be the action on the ground that improves the resilience and increases the efficiency of our agriculture and food systems.

Sources: Aim For Climate; CGIAR; Food4Climate Pavilion; Food Systems Pavilion COP27; IFAD; IICA; New Zealand Government; Odepa-Chile; Relief Web; The Rockefeller Foundation; United Nations Climate Change; UN FAO; USDA; WHO

Photo Credits: Photos taken at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27), used with permission and courtesy of Kelly Witkowski.

Note: This article originally appeared on New Security Beat at https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/11/cop27-growing-roles-agriculture-food-security/

Kelly Witkowski is the Manager of the Agricultural Climate Action and Sustainability Program at the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture

Kelly Witkowski is the Manager of the Agricultural Climate Action and Sustainability Program at the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture

Note: The opinions expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of IICA.

|

If you have questions or suggestions for improving the BlogIICA, please write to the editors: Joaquín Arias and Viviana Palmieri. |

Add new comment