Multilateral trade negotiations over agriculture present a complex set of challenges: Finding a balance between the diverse interests and positions of the 164 members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) is exceedingly difficult due to the importance and varied sensitivities of this sector across countries. Those with significant agrifood exports want new market opportunities and thus promote greater trade liberalization; other members, generally importers, prefer to focus on increasing domestic production and protecting their domestic markets.

As a result of these differences, recent agricultural trade negotiations have moved slowly—and sometimes not at all. Only two ministerial decisions related to agriculture, focusing on export restrictions, were approved at the June 2022 12th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC12) in Geneva. While those moves were positive and timely, no progress was made on the eight negotiation topics of the WTO’s agricultural program, including domestic support, market access, and public stockholding for food security. Required work programs to guide post-MC12 negotiations for domestic support and public stockholding (PSH) programs were not discussed at all.

Latin American WTO member countries were particularly disappointed by this outcome. They have made significant efforts to increase their participation in the international market through enhanced competitiveness, innovation, and the implementation of policies and programs in line with the WTO’s “rulebook.” They were ready to move forward, yet progress remained elusive. Although most WTO Members agree on the need for further reforms or clarifications of the agricultural trade disciplines, serious differences remain, requiring ongoing efforts to fulfill the mandate of the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA).

Yet the process continues. With MC13 set for February 2024 in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Latin American countries are continuing to advance a broad set of agricultural trade reforms. In this post we note the key role the region plays in global agricultural trade and outline its reform efforts and the challenges they face.

Latin America and global markets

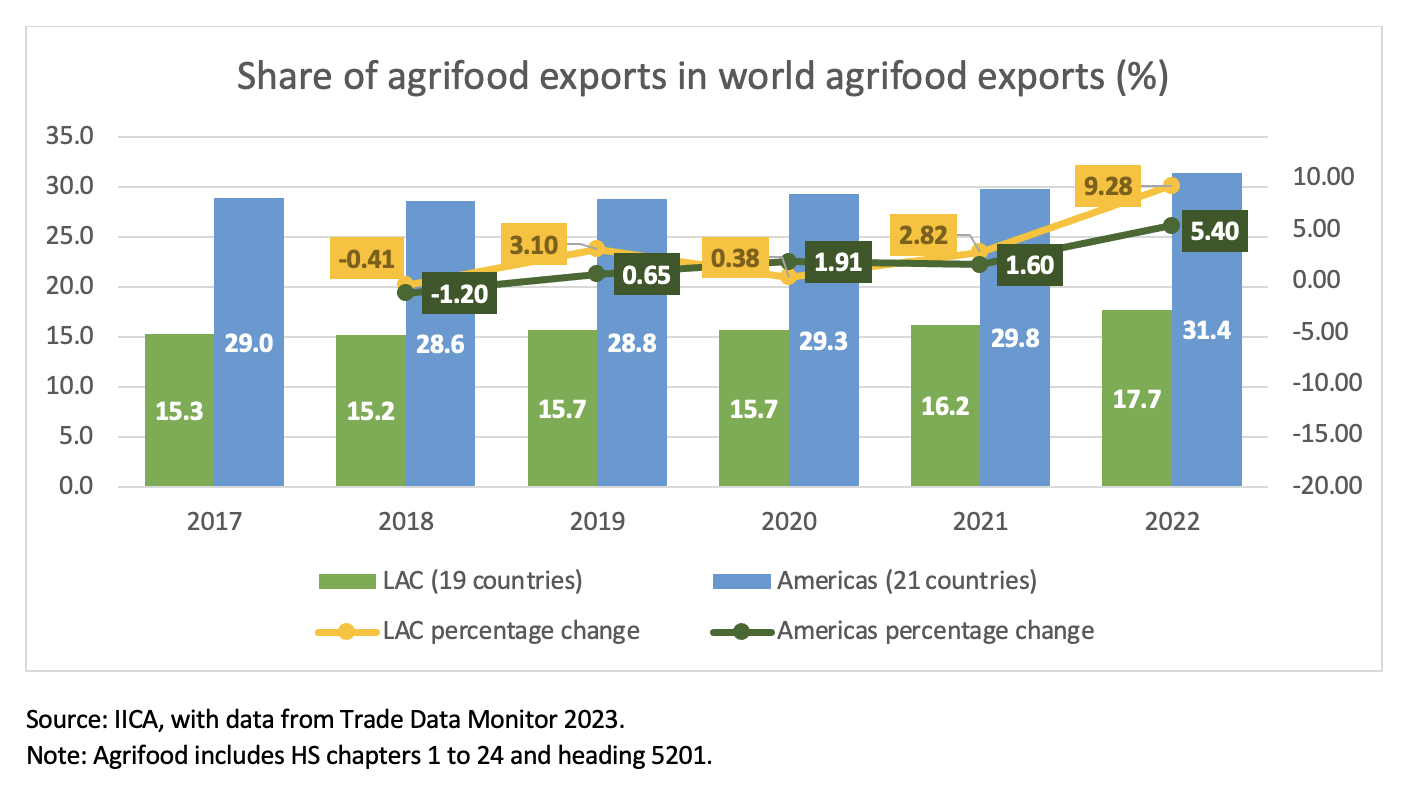

Latin America plays a major role in global food production and trade, and many countries in the region are eager to deepen agricultural reform. In 2022, the combined agrifood exports of 19 Latin American countries1 accounted for 17.7% of the world total. When combined with those of the United States and Canada, the Americas as a whole accounted for 31.4% of global agrifood exports (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Note: LAC (19 countries): Argentina, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

|

“The region has proved relatively resilient in the face of multiple crises, with agrifood exports continuing to rise despite COVID-19 pandemic disruptions in global value chains (GVCs), extreme weather events, and the global repercussions of the Russia-Ukraine war.” |

Trade reforms

So, it is not surprising that Latin American countries have actively pursued agricultural negotiations, presenting many individual and ambitious group proposals. Over the two years leading up to MC12, countries in the region co-sponsored 62 out of a total of 97 proposals (Figure 2). The efforts reflect the region’s collective commitment to work to achieve progress in in all three AoA pillars to achieve open, predictable, and functional agrifood markets in line with AoA Article 20.

In general, the proposals seek to integrate local, regional, and global supply chains, and eliminate trade-distorting practices and protectionist measures that hinder the proper functioning of as GVCs and market access, severely impacting the production and exports of developing countries.

Note: Agricultural proposals pertaining to the seven negotiating topics were included in the analysis: Domestic support, market access, export competition, export restrictions, cotton, special safeguard mechanism and public stockholding for food security purposes. Unofficial room documents, technical analysis, notes by secretariat and commitments were not considered. To count the agriculture proposals, an approach based on the negotiating topic level was adopted. This meant that a single document could contribute to more than one count if the proposal addressed multiple negotiating topics.

The proposals from the LAC region have focused on the following areas:

Domestic support: The region aims to strengthen existing disciplines and reduce levels of trade-distorting support, proposing a cap on existing support levels and a process to reduce them over a determined period. Their goal is to decouple domestic support from production. The proposal of Costa Rica follows a principle of proportionality in reduction—members with higher levels of trade-distorting support undertake greater reduction commitments—seen as a creative criterion to facilitate agreements. Attention is also given to the needs of low-income and resource-poor farmers in developing countries, as outlined in Article 6.2 of the AoA, which exempts them from support reduction commitments.

Market access is no longer the top priority in agricultural negotiations due to lower global tariff levels and the influence of free trade agreements. However, there are still issues to be addressed, such as comprehensive market access and new disciplines. One Latin American proposal would substantially increase market access for agricultural products within ten years, with transparency and moderation emphasized to prevent the misuse of non-tariff measures. Ensuring transparency in market access reforms is also highlighted.

Public stockholding (PSH) for food security has been a highly contentious issue in agricultural negotiations. Developing countries have expressed legitimate concerns regarding their need to address internal food security needs through public purchases of key staples. The WTO adopted temporary measures in 2013, providing flexibility and a mandate to develop a permanent solution. Latin American countries have raised concerns about proposed permanent and called for continuing dialogue. In particular, LAC countries are concerned by the possibility of publicly-held stocks moving into export channels, lowering market prices. The region's well-supported technical proposals acknowledge the need for PSH programs under certain conditions, with rigorous safeguards, anti-circumvention clauses, and prohibitions on the inclusion of such purchases in the country's export supply while ensuring they do not undermine other countries' food security objectives.

Export restrictions: Food security concerns have arisen as some countries have imposed export restrictions to protect local supplies and producers amid recent global challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the container crisis, and the Ukraine-Russia conflict. Such restrictions can contribute to higher international prices of key commodities and harm net food-importing developing countries. Latin American countries have strongly advocated for concrete results on this issue. Consensus was reached at MC12 to exempt purchases made by the World Food Program (WFP), a resolution that had been under negotiation for many years. Another ministerial resolution emphasized the need to align export restrictions with provisions in the AoA and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, ensuring that such measures are specific, temporary, and the WTO duly notified.

|

“It is crucial that steps taken to address export restrictions maintain open and transparent agricultural markets and effectively address food price volatility without imposing restrictive or distorting measures. The region has also emphasized the importance of providing food aid in the form of full donations, based on actual needs, to prevent trade displacement and adverse effects on local and regional production and markets.” |

Transparency is crucial to the effective functioning of the multilateral trading system, yet some countries do not consistently comply with mandated notification requirements for certain trade measures. Transparency should be upheld throughout the entire process of meeting commitments. In agricultural negotiations, some Members have said they do not have sufficient capacity for making such notifications, lacking both the infrastructure and skilled personnel necessary to capture the required information. Over time, it has become evident that certain information, such as the production value of certain crops, should be included in notifications to provide trading partners with a better understanding of the impact of public policies and programs. The Latin American countries have proposed that the Secretariat provide greater support and concrete assistance to Members to facilitate compliance. In addition, a proposal suggesting concrete sanctions for non-compliance after specified deadlines has gained significant support from many countries in the region.

The path to MC13

IFPRI and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) recently launched a network of agricultural negotiators in Latin America. The initiative seeks to create an informal space for exchange on the current state of negotiations in agriculture ahead of know the interests of the different actors; and assess the possibility of forming a network of agricultural experts responsible for trade policy in Latin America led by the delegates prominent in Geneva, including senior government officials from across the region.

|

“IICA and IFPRI, in their capacity as international organizations whose mission is to provide technical cooperation to member countries, make their technical and convening capacity available to the Latin America agricultural delegates to support this process for MC13.” |

Is worth mentioning the prominent role that the region, in general, plays in the WTO, especially in agricultural negotiations, which is crucial for making progress on the agenda. In recent years, the focus has shifted from incorporating agriculture into the international trade "rulebook" to addressing new priorities and topics such as post-COVID-19 recovery, food security, and the relationship between climate change and sustainability. This triad of issues will inevitably form the reference framework for future agricultural trade.

Conclusion

A lack of progress does not necessarily mean failure; avoiding a poor decision can be a good outcome. WTO Members share broad priorities such as working towards reducing trade and production distortions and the need to reform agrifood systems to promote rural well-being and ensure food security. More efficient and equitable markets also help strengthen productivity, create jobs, and increase rural incomes.

With another conference approaching, Members in Latin America and elsewhere are emphasizing the need for a robust outcome in agriculture—but perspectives still differ significantly on how to achieve it. We hope the coming months will clarify that picture, but the major challenge facing agricultural negotiations in the WTO remains an absence of trust, transparency, and political will.

Gloria Abraham Peralta is a Consultant with the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) and former Costa Rica Ambassador to the WTO and chair of the WTO agriculture negotiations.

Gloria Abraham Peralta is a Consultant with the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) and former Costa Rica Ambassador to the WTO and chair of the WTO agriculture negotiations.

Adriana Campos is a Senior Trade Specialist with IICA's Directorate of Technical Cooperation.

Adriana Campos is a Senior Trade Specialist with IICA's Directorate of Technical Cooperation.

Valeria Piñeiro is Acting Head of IFPRI's Latin America Region and a Senior Research Coordinator with the Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit.

Valeria Piñeiro is Acting Head of IFPRI's Latin America Region and a Senior Research Coordinator with the Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit.

Elsa Olivetti is Research Assistant with IFPRI's Markets, Trade and Institutions Unit (MTI).

Elsa Olivetti is Research Assistant with IFPRI's Markets, Trade and Institutions Unit (MTI).

Note: This article appeared first at IFPRI Blog : Issue Post.

The opinions expressed in this article are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of IICA.

|

If you have questions or suggestions for improving the BlogIICA, please write to the editors: Joaquín Arias and Eugenia Salazar. |

Add new comment