The vulnerability of agrifood systems to production concentration, trade and consumption

Globalization has given rise to more complex and integrated agrifood systems that generate synergies, on the one hand, but that are also vulnerable to political, environmental and economic disruptions or to conflicts, such as the one currently unfolding between Ukraine and Russia. According to the UN, the Ukraine invasion has resulted in the displacement of more than 2.2 million people and the Ukraine’s Emergency State Service has reported more than 2,000 civilian deaths.

Agrifood systems are particularly susceptible when conflicts arise in geographic areas where the importance or concentration of production, trade or consumption is high. Consider for example that Ukraine and Russia together account for 14% of global wheat production and close to 30% of exports (Russia and Ukraine are the leading and fifth leading exporters, respectively, selling mainly to countries in Asia, Africa and the European Union). On the other hand, Ukraine is among the world’s four top exporters of corn, along with the United States, Argentina and Brazil, with most exports destined for Asia, Africa and the European Union.

The world is extremely vulnerable from a food security perspective, considering that more than 40% of the calories consumed globally are from three crops: wheat, corn and rice. Specifically, 20% of the calories consumed are from wheat, and in some places, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Mesoamerican, Northern Africa and Andean regions, to name a few, corn consumption as a percentage of total grain consumption ranges from 73%, 46%, and 39% to 36%, respectively, not to mention its importance for animal feed.

|

“The effects of the armed conflict, combined with the repercussions of COVID-19 and adverse climate conditions are considerable shocks to the world’s agrifood systems”. |

The armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine has triggered the closure of ports and has practically paralyzed economic activity in the Ukraine. This has also prompted the imposition of international economic sanctions on Russia, including trade restrictions and the partial exclusion of Russian banks from the SWIFT financial transaction system. The effects of this crisis are a further blow, on top of the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic and extreme climate events that had already altered the supply and normal flow of products and services, creating galloping inflation around the world, particularly for food. This was partially due to disruptions in global supply chains and significant international price increases. For example, prior to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, prices for yellow corn in the United States were on the rise in January and February, due to freight costs and increased demand. In Argentina and Brazil, an upward trend in prices since August 2021 accelerated in January and February, given concerns about the impact of dry conditions on crop output.

The effects of the armed conflict, combined with the repercussions of COVID-19 and adverse climate conditions are considerable shocks to the world’s agrifood systems, which have been affected through at least four transmission channels or routes.

Agrifood trade in Latin America and the Caribbean will be minimally or at least not directly affected

The first transmission channel will be restrictions to agrifood trade, given that Russia and the Ukraine together represent 30% of global wheat exports and 20% of corn exports. As mentioned before, this would significantly undermine the food security of millions of people, especially in countries in the Middle East and Northern Africa, which are dependent on imports from these countries. Moreover, Russia and the Ukraine together account for more than 70% and 25% of the global volume of sunflower oil and sunflower seed exports, respectively, and 30% of barley exports.

However, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) will be minimally or at least not directly affected by these agrifood trade restrictions, since Russia only accounts for 1.5% of total exports from the region (primarily for soybean and banana, amounting to more than a billion US dollars, as well as for beef and fish) and 0.17% of imports. These figures are even less in the case of Ukraine (a country that imports mainly banana from LAC, valuing more than 200 million dollars). Thus, the impact of the crisis on trade in the region will be felt indirectly, primarily through the redirection of trade; but this does not change the fact that some LAC countries may be more directly affected than others. For example, there is Nicaragua, which imports large amounts of Russian wheat; Ecuador, which exports fruits (Russia is its primary market for overseas banana sales), plants and flowers to Russia; and Colombia and Paraguay, whose main destination market for frozen beef is Russia.

On the other hand, disruptions in Russian exports may cause trade to be redirected and may open up export opportunities mainly for countries that export milling products, grains, fats and oils and oilseeds. For example, commercial partners most affected by the crisis, one of them being the European Union—destination market for 22% of Russian agrifood exports—will have to turn to other markets. A country like Spain, which will be most affected by its dependence on Ukrainian corn imports—a key and strategic component in the preparation of feed for its livestock sector—has launched an advocacy campaign in Brussels, calling for exceptional measures to guarantee the supply of grains. For example, it is proposing the relaxation of requirements governing phytosanitary products and transgenics that are not allowed in the European Union, thus opening up itself to other markets. This could benefit economies such as Brazil and Argentina, in the short-term.

In this scenario of redirected agrifood trade, it is vitally important that the Chinese market be monitored, given its importance to global trade. Its recent agricultural agreement with Russia will allow it to import wheat from that country, which could affect imports from western countries such as Canada. Moreover, as stated above, Ukraine supplies close to 30% of total corn imports into China. Therefore, it would not be surprising if China had to turn to the United States market to offset any shortfall, as it has in recent years. On the other hand, the Russian Federation notified the World Trade Organization that it has lifted provisional restrictions on imports of fresh apples, pears, quinces, apricots, cherries, peaches, nectarines, cherries and sloes from China.

|

“The way in which countries respond to this crisis may exacerbate its effects” |

Finally, the way in which countries respond to this crisis may further exacerbate its effects. Countries could adopt trade restricting measures out of fear that the conflict may cause a global shortage of products, which would worsen the high price scenario and adverse conditions, thereby impacting food security in countries that are extremely vulnerable and those that are import dependent. Early signs of protectionism are the ban on grain exports by Hungary and Serbia’s announcement regarding the detaining of ships departing its shores. Other countries in the region have announced measures to better control the local supply.

Most Latin American and Caribbean countries will be affected via trade restrictions and higher prices for fertilizers

The second transmission channel or route for the effects of the crisis is the trade in and price of fertilizers. These prices were already increasing, even prior to the war, as a result of increases in petroleum prices. Russia produces enormous quantities of nutrients, such as potassium and phosphate, ingredients that are key to the production of fertilizers that enable plants and crops to grow. Most LAC countries will be affected via trade restrictions and increases in production costs, particularly Brazil, which imports 85% of its fertilizers from that region and uses more potassium-based fertilizers for soybean production than the United States or Argentina. Other countries that could be severely affected are Peru, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Suriname, given their great dependence (more than 60%) on nitrogen fertilizer imports from Russia and Belarus.

The increase in international prices for basic products will be detrimental mainly to those countries in the region with a high level of vulnerability to food insecurity

The third crisis transmission channel is the accelerated growth in international prices for basic products, which calls for a separate analysis, given that it directly and indirectly affects countries that have no trade relations with Russia or the Ukraine. As a results of the accumulated shocks, some related to Covid-19, others to severe droughts and now the armed conflict, prices for wheat futures increased 45%, for corn 18% and for soybean 11%, during the period from 1 February to 7 March 2022. These significant price increases could benefit net exporters in the region, primarily of grains, but will be detrimental to low-income countries and net food importers, which were already been buffeted by inflation. The situation is critical, given that, before the armed conflict, countries in the region had accumulated an average inflation rate of 7.1%, as at November 2021 (excluding Argentina, Haiti, Suriname and Venezuela), led by increases in food and energy prices.

The prices of both international commodities and substitute products are on the rise. For example, in the Central Region, there is a fear that elevated international prices for yellow corn will push up local prices for white corn, due to the increased demand in the food and feed industries. A similar situation will occur with other substitute products, with the consumption of food such as rice, potato and others.

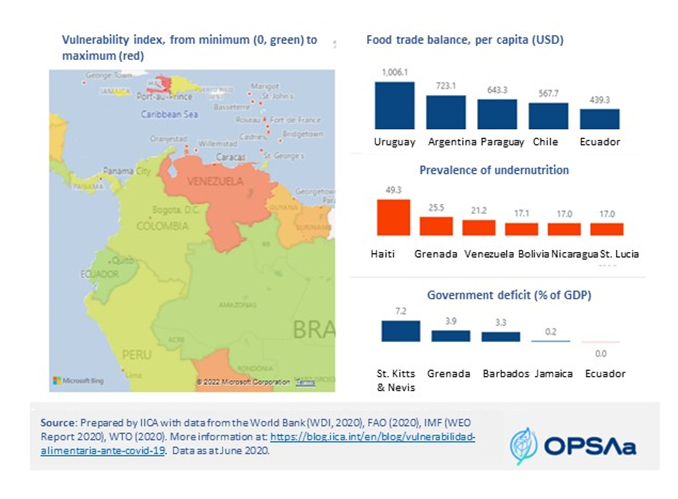

This upward trend in international and domestic prices, as well as potential trade restrictions, will be detrimental mainly to countries in the region that are extremely vulnerable to food insecurity, mostly due to their status as net food importers and the high prevalence of undernutrition. Falling under this category would be certain Caribbean countries, particularly Haiti, Grenada and St. Lucia, and LAC countries, such as Venezuela, Bolivia and Nicaragua, as the countries with the highest levels of undernutrition.

Increases in energy prices will have a multiplier effect on costs for production and services throughout agrifood chains

Finally, and of no less importance, the fourth crisis transmission channel is the increase in energy prices, which will trigger a multiplier effect on production and service costs throughout the agrifood chains. To cite just one example, the increase in petroleum prices has produced a 70% increase in maritime transportation costs. Of greater concern, according to some specialists, is that the war could triple maritime freight rates from USD 10,000 to 30,000 per 40-foot container, at a time when the world is just beginning to recover from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

“The armed conflict has left no room for doubt about the need to strengthen and make the necessary adjustments in our agrifood systems, to build resilience against future risks”. |

Global integration of agrifood value chains further complicates any analysis regarding future disruptions that these or other crises could have on agrifood systems. The armed conflict has left no room for doubt about the need to strengthen and make the necessary adjustments in our agrifood systems, to build resilience against future risks.

Sources and supplementary reading

- Trade Data Monitor http://www.tradedatamonitor.com/

- BBC, 2022

- BBC, 2022

- USDA, Feed Outlook, 2022

- Financial Times, 2022

- OndaCero,2022

- LaRazón, 2022

- University of Illinois, 2022

- University of Illinois, 2022

- IFPRI, 2022

- Agrofy News, 2022

- ElPaís, 2022

- ElPaís, 2022

- EuropaPress, 2022

- VOA, 2022

- ING, 2022

- Agrofynews, 2022

- Red Regional de Información de Mercados (RRIM), Informe de mercados de granos Básicos para Mesoamérica y Caribe, teleconferencia, marzo 2022.

Note: The opinions expressed in this blog are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of IICA.

Joaquín Arias holds a PhD in agricultural economics from Oklahoma State University (OSU), United States. He is an international technical specialist at IICA's Center for Strategic Analysis for Agriculture (CAESPA), based in Panama.

Joaquín Arias holds a PhD in agricultural economics from Oklahoma State University (OSU), United States. He is an international technical specialist at IICA's Center for Strategic Analysis for Agriculture (CAESPA), based in Panama.

Carlos Ruiz is a graduate of the Complutense Universidad of Madrid and the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), with a Master in Strategies and Technologies for Development. Currently, he is an international consultant at IICA.

Carlos Ruiz is a graduate of the Complutense Universidad of Madrid and the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), with a Master in Strategies and Technologies for Development. Currently, he is an international consultant at IICA.

Silvia Castellano has a Master’s degree in Strategies and Technologies for Development from the Complutense Universidad of Madrid and the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) and is undertaking a professional internship with IICA.

Silvia Castellano has a Master’s degree in Strategies and Technologies for Development from the Complutense Universidad of Madrid and the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) and is undertaking a professional internship with IICA.

Daniel Rodríguez Sáenz, Manager of IICA’s International Tarde and Regional Integration Program.

Daniel Rodríguez Sáenz, Manager of IICA’s International Tarde and Regional Integration Program.

Eugenia Salazar, Technical Specialist, IICA's Center for Strategic Analysis for Agriculture (CAESPA)

Eugenia Salazar, Technical Specialist, IICA's Center for Strategic Analysis for Agriculture (CAESPA)

|

If you have questions or suggestions for improving the BlogIICA, please write to the editors: Joaquín Arias and Viviana Palmieri. |

Blog comments

Impacto de la guerra en la agricultura

El conflicto armado quien se beneficia son las organizaciones financieras quienes se ven afectados son los sectores que tienen que están relacionados con los problemas alimentarios es decir el agroindustria por lo tanto se genera desempleo caida de los ingresos e impactos negativos en la política fiscal y monetaria .Por ello no deja lugar a dudas sobre la necesidad de fortalecer y realizar los ajustes que estos sistemas agroalimentarios requieran para desarrollar resiliencia a riesgos futuros.

Add new comment